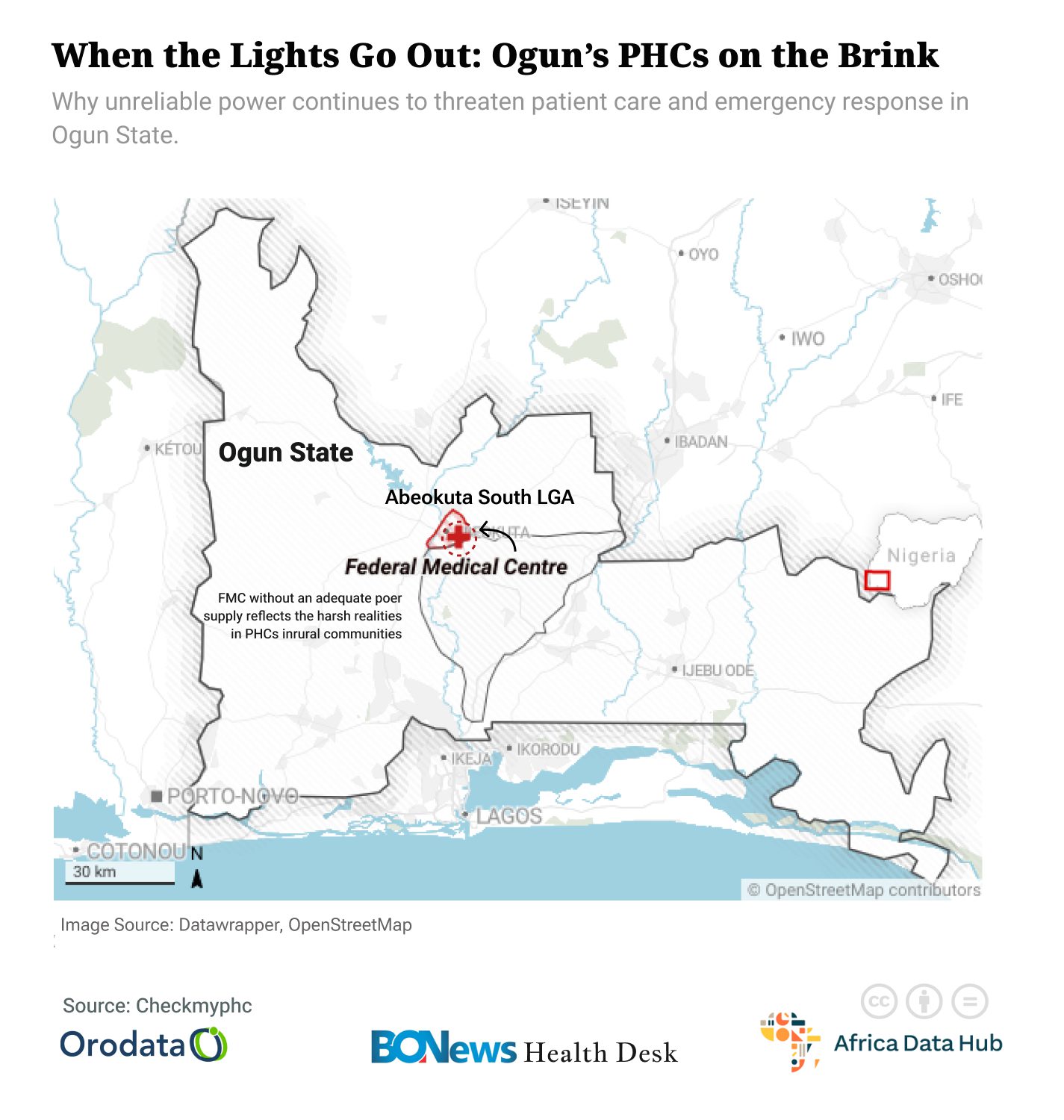

When the lights went out during a dental extraction at the Federal Medical Centre, Abeokuta, on October 27, 2025, the operation was abruptly halted. The dentist stopped after already making an incision because both the hospital’s power supply went out and the backup generator was faulty. The patient was left in severe pain and unable to complete treatment until a later date.

Unlike the Federal Medical Centres (FMC), which are expected to be well-equipped to provide tertiary healthcare services to citizens, Primary Health Centres (PHCs) are the first point of care for millions of Nigerians.

An FMC without an adequate power supply reflects the harsh realities in PHCs in rural communities, where residents seek immediate help in moments of medical distress.

Orodata’s CheckMyPHC portal and the State of Power in Primary Healthcare report reveal the troubling picture of how healthcare, the most basic requirement for delivering healthcare, remains unreliable or completely absent.

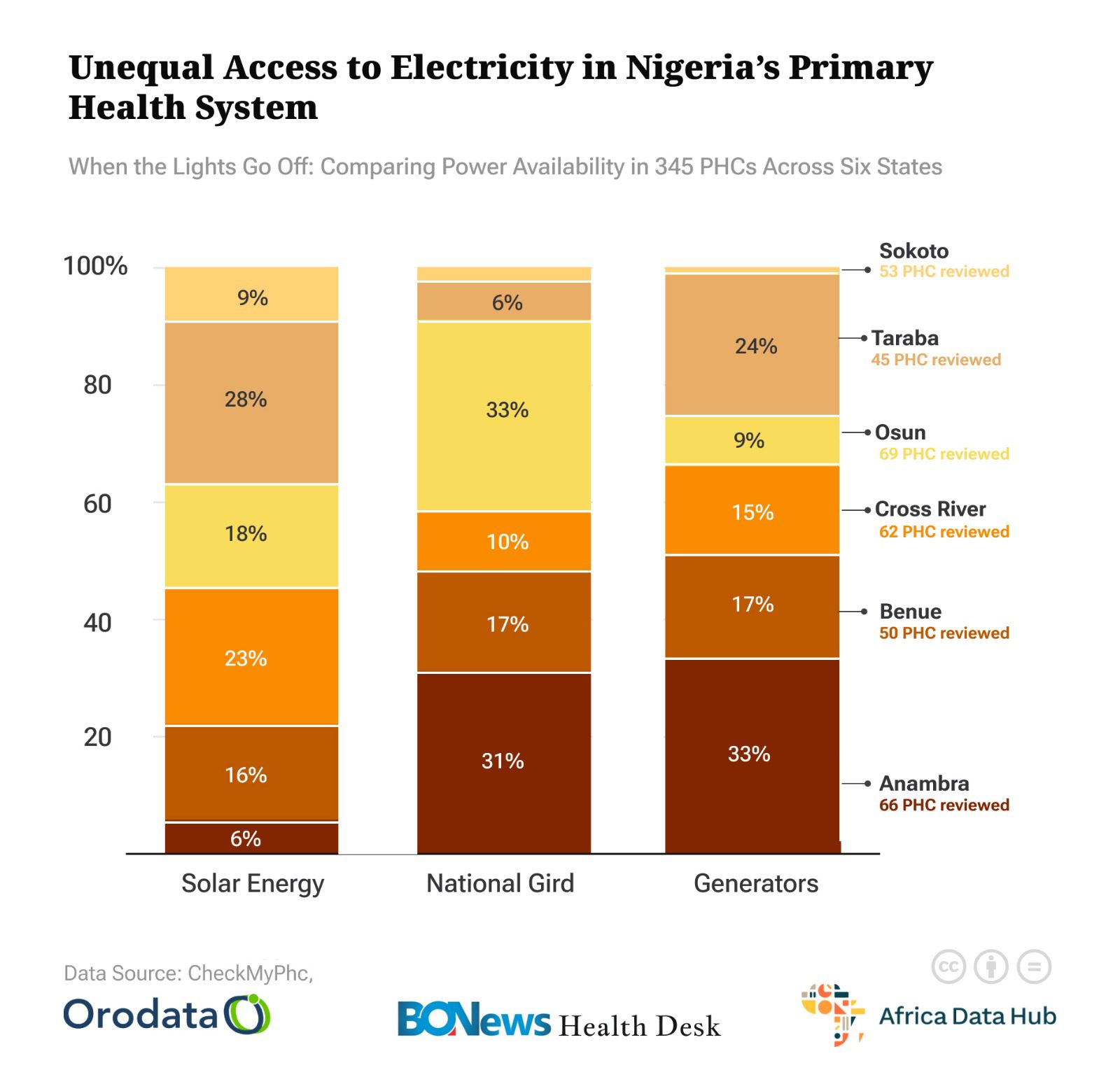

The data, drawn from 345 PHCs across Osun, Anambra, Benue, Cross River, Sokoto, and Taraba States, shows that two out of every three facilities do not have a reliable source of power. Only about 45 per cent are connected to the national grid, and even among these, power supply is so inconsistent that health workers still struggle to keep operations running.

The report shows that 66% of PHCs operate without any electricity, and 34% have at least one power source. The power sources in these PHCs are different, as only 25% of the PHCs are connected to the national grid. Thirty-five per cent have generators as their backup power, with 15% of donor-supported PHCs having solar power. Community members are providing power to 5% of the PHCs, and 10% have a hybrid power system that combines solar and grid power.

The assessment revealed that many centres rely on petrol or diesel generators that can only be switched on during critical emergencies because fuel costs are prohibitive. Others depend on lanterns, candles or whatever light source is available at night. Some facilities have solar installations, but they are far too few to address the widespread energy gap across these six states.

Despite the differences in geography or population, the pattern is consistent everywhere: reliable power is the rare exception rather than the norm. This reality echoes findings from broader assessments, which estimate that a significant share of PHCs across Nigeria lack reliable electricity or renewable-powered backup.

Power cuts and daily healthcare

This chronic power shortage carries consequences far beyond inconvenience—electricity is essential to nearly every aspect of primary healthcare. Without stable power, vaccine refrigerators fail, putting thousands of doses at risk and disrupting immunisation schedules that communities rely on to protect their children. Mothers in labour often deliver in semi-darkness, guided only by a nurse’s phone torch or the flicker of a kerosene lamp.

Specifically, the report indicates that 83% of the PHCs are unable to support emergency oxygen therapy, and 6% lack refrigeration due to a power shortage.

These conditions increase the risk of complications and force health workers to make difficult decisions about whether to continue a procedure or attempt a referral to a distant hospital, one that many families cannot access in time.

Speaking about the impacts of power shortages on healthcare delivery, a laboratory technician, Mr Ayomide Adeyemi, said that inadequate or non-availability of power supply in primary health centres can pose serious risks to both patients and laboratory equipment.

Adeyemi said, “When there is inadequate power supply, essential equipment such as microscopes, centrifuges, incubators and analysers cannot function properly and could lead to delayed test results, incomplete diagnosis and in some cases, total inability to detect health conditions.”

He also noted that poor power supply can damage some cold-chain items, especially vaccines, and added that “in emergency cases such as childbirth, any delay caused by poor power supply can directly endanger lives.”

Similarly, Dr Adeolu Olusodo, Medical Director at Atayese Hospital, Odongbolu, said many PHCs cannot operate effectively at night because there is no lighting, and essential equipment such as suction machines, sterilisation tools, or oxygen concentrators cannot function without power. Dr Olusodo buttressed that,

“The importance of stable electricity in primary health centres cannot be overemphasised because there is no way the health team can render quality healthcare services if there is no power supply. In Ogun State, especially in Ijebu, many of the PHCs have been fitted with solar systems, but unfortunately, some of these solar systems are no longer effective and cannot provide power for a long period of time.”

He noted that many of the PHCs have to make do with rechargeable lamps to deliver services, which, according to him, is not efficient and affects procedures.

Universal Health Coverage at risk

Beyond individual suffering, the power crisis threatens broader national health goals. According to the World Health Organisation, PHCs are meant to be the bedrock of accessible, affordable care — the foundation for achieving universal health coverage.

However, when the PHCs can’t guarantee basic infrastructure such as reliable power, the promise of equitable healthcare becomes hollow. The gaps exposed by electricity failures underscore significant issues in planning, funding, and maintaining healthcare infrastructure across states.

Although official programs aim to revive PHCs under a comprehensive strategy of functional upgrades, including power facilities, many remain unfulfilled or only partially implemented.

Solar solutions and way forward

In some PHCs that have access to solar power, staff describe a transformation: consistent lighting, working vaccine fridges, functional laboratories, and active labour rooms. Patients in those communities report more confidence in the health centre and more regular attendance.

These examples demonstrate that solutions exist and are within reach, but remain too few in comparison to the scale of the problem.

According to Dr Olusodo, “strengthening primary healthcare delivery in Nigeria requires more reliable and sustainable power than equipment donations or infrastructure rehabilitation.”

He said, “Apart from ensuring that public power supply is stable, the government needs to service the solar systems where they are available or set them up in PHCs that do not have solar at the moment. This needs to be done urgently to ensure that there is up to 24 hours of power supply in PHCs so they can provide quality healthcare at the grassroots.”

Solar systems and renewable energy solutions offer a realistic alternative, especially in rural settings where grid supply is weak or nonexistent. But expanding such infrastructure will require deliberate investment, proper maintenance, stronger accountability, and political will to ensure that every PHC can deliver the quality of care it was designed for.

The data from CheckMyPHC, along with the State of Power report, show that electricity is not a luxury in healthcare, but the backbone of safe, effective, and humane service. Without it, the promise of primary healthcare remains out of reach for millions of people.

If Nigeria hopes to protect vulnerable populations and make meaningful progress toward universal health coverage, powering PHCs must become a national priority. Until then, communities across these six states will continue to confront a dangerous reality: when the lights go out, healthcare falters, and lives hang in the balance.

This story was produced by the BONews Health Desk, supported by the Africa Data Hub and Orodata Science.