Gideon Adeyeni is an environmental and social justice activist whose commitment to progressive ideologies has shaped his personal and professional journey. Gideon is committed to propagating progressive ideas such as socialism, minimalism, veganism, humanism, and feminism. In this insightful interview with Blessing Oladunjoye, Gideon shares the transformative experiences that sparked his activism, the societal challenges he faces in Nigeria, and the resilience required to champion these often misunderstood and marginalized beliefs.

Blessing: Pleased to meet you, can you introduce yourself?

Gideon: Yes. My name is Gideon Adeyeni. I’m an environmental and social justice activist. I’m from a family of 6. I have some academic qualifications. I recently completed a Doctor of Philosophy Degree in Urban and Regional Planning at the University of Ibadan, Nigeria. I have a Masters degree from Obafemi Awolowo University and a first degree from Ekiti State University. What else? I am a socialist, vegan, humanist and so forth. Essentially, I am committed to a number of progressive ideas/philosophies – veganism, humanism, socialism, feminism, minimalism among others.

Blessing: Thank you. Can you speak about your ideologies, and specifically about how you maintain commitment in a place like Nigeria where those ideas are not so popular?

Gideon: Yes. You know, progressive ideas are not very popular here, like you rightly noted. And commitment to them are so rare. So that when an individual maintains very strong commitment to these ideas, one gets attacked. These ideas are described as radical ideas and those who are committed to them are still tagged as radicals, even though we are in the 24th century.

For instance, sexism is so entrenched in our society even today. Many people still believe that certain gender category is superior to another, and this is well expressed in our religious institution and in our society generally. Let’s take a look at the political structure of our society. Those who occupy the seats of government are mostly men. Perhaps over 95% of those who occupy our seats of government at the executive and legislative level are men. Check out the religious institutions, those who head those institutions are men. Sexism is is a core part of the ideas upon which our social systems are based. When one does not subscribe to it, I mean that if one believes that men and women are equal, as I do believe, and one maintains that opportunities should not be denied to anyone because of the kind of genitals they possess, one is deemed to be a radical. And it’s it’s rather unfortunate.

Another instance, if anyone believe as I do, that the resources of the society should be judiciously used for the good of all, that a few people should not hold so much wealth while many people languish in poverty and penury in the society, when one believes that the workers whose labor generates wealth should decide how that wealth should be shared, which is what socialism is about, one is deemed to be a radical. It’s rather unfortunate that all of these progressive ideas, which are the bases upon which a just society can be built, are still very unpopular in this part of the world.

But growing up, I just realized that I could not but commit to these ideas. I couldn’t just do otherwise. I tried doing otherwise but I could not. Let me cite a simple instance of what I mean by I tried but I could not. As a young boy I tried lying. When I committed some mistake I would lie about it. But then I realize that I forget things. So if I say I didn’t do this today and after a while. Then later I will say something like “remember when I broke that pot…” and then it would be revealed that I broke the pot. Because I would have forgotten that I actually said that I didn’t break the pot. So, growing up, I just realized that I could not do otherwise, but to find out and commit to progressive ideas and then try to improve my commitment to these ideas.

Blessing: So you just talked about your experience growing up. How did you start your activism? I believe your socialization is quite important. The society basically shapes us. So how did you get involved in all of these beliefs and commitment to progressive ideas?

Gideon: Well, I was born into a religious home. My mum is a very conservative – what they call devout – Christian. My dad is not a radical Christian. He was going to church, but he would question many things. I remember that at a point I told my dad that: “if you say I’m too radical today, you should remember the time when you held my hand as a young boy, and told me stories of how you refused to submit to some authoritarian somewhere, or how you would say something like ‘I disagree with what that pastor was/is saying’. That was communicating that it is right to question authority, even and especially religious authority.” So, the seed of any radical idea or character that I may possess today, I think, was planted largely at home.

But also, growing up, I was exposed to some literature, writings and stories that helped my radicalization. I remember that growing up, my dad would talk about the Mandelas and Thomas Sankaras of this world. He was actually nicknamed Obote while in secondary school, I think. Obote was one of the post-independent African leaders. So, he told us that it was in history or geography class that they were asked to memorize the names of the post-independence African leaders. To be able to easily memorize it, they decided to take the names of the leaders as nicknames, and he became Obote. We will always talk about those leaders, and of course, we would dwell on Thomas Sankara, Kwame Nkrumah and co. So, I think my dad had a great influence on me and even on the literature which I picked up interest in and became exposed to.

At a certain age, in post-secondary school basically, I started reading about these characters and many others. I read about Nelson Mandela, Mahatma Gandhi, Martin Luther King Jnr., Malcolm X and Co. I also read about Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels and so forth. In summary, I think that family and then the kind of books that I was exposed to had a strong influence on me.

I also feel that my socioeconomic background had an impact. I was born into a very lowly family. We were living in poverty in the midst of plenty. The neighbourhood that we were staying in in the 90s, most of the people there were professionals, doctors, pharmacists et cetera. They had cars, modest houses. But we were living in a mud house, with iron zinc door. I mean that the zinc sheet used for roofing was used to make our door. We were living in that kind of house in an affluent neighbourhood. But despite that poverty, my dad would ensure that his children got the best kind of education that he could afford. Even if it meant skipping meals on too many occasions, he ensured that he paid our school fees. All four of my parents’ children attended private schools from nursery, primary to secondary level. It didn’t come easy. It meant that we went hungry at some point. But I think that the interaction of that education with the exposure to poverty, which is a product of the oppressive system that we live within, moulded my mind. Yes, I was and I am angry. I hated and I still hate poverty. I would say it locks up human talent. But I have also come to understand that it is through creative actions that societies are transformed. My education and readings brought me in contact with the concept of civil resistance. And today, what I basically do is to mobilize people for civil resistance actions and campaigns as the pathway to transform unjust systems and societies that we live within.

Blessing: I think you are already going into my next question, which would be about your civil resistance actions. What are some of the key actions that you’ve taken to speak against injustices in the past?

Gideon: Challenging systems, essentially, means speaking up. This can take various forms. One could sing it. One could make a film to expose an injustice or challenge a system or practice. One could do many other things. For me, it has basically taken the form of writing and mobilizing for and partaking in civil resistance actions. I write on social media, and I share my thoughts with journalists who publish them freely. Thoughts that many are afraid not to share, I share them freely. I speak freely about what I think is right. When social media came, I started expressing my thoughts on social media freely, and when the opportunity comes, with journalists in the mass media. Beyond this, I try to mobilize for civil resistance actions. Sometimes I simply join actions.

In 2021, I was working as a secondary school teacher, earning a meagre salary of about #45,000, yet I took transport from Ile-Ife down to Lagos to join a mass action. So, usually, I join mass actions, and I mobilize for same.

I started my PhD at the Obafemi Awolowo University in 2016. Sometime in 2017, a friend approached me and told me about how after some postgraduate students have defended their thesis/research they are made to pay some unjustifiable fees. The issue primarily was that results are approved by the university senate, which could take up to 2 or 3 semesters after the defence. Whereas the students have no control over the administrative process involved. We called a meeting, and the postgraduate students agreed that this was not right. Students felt that they have no control over the process, which often keeps students delayed, and instead of penalising students for this, students should be compensated. So, we started a campaign which we called “Say No to OAU PG Exploitation”. So, the campaign lasted for a couple of weeks. We wrote letters, had meetings, and invited the provost, but our demands were not met. So, we decided on mass action, and we marched from the postgraduate hall of residence to the postgraduate college. The college subsequently issued what they call a “studentship termination letter” to four of us who were among those who led the campaign. After a few weeks, I can’t remember the precise number, they issued another letter reinstating us.

But earlier before then, in 2016, I had gotten feelers that I was not going to finish my PhD at the university. A professor actually approached me and said “if I were you, I would not have come back to this university”. Actually, during my master’s degree programme, there was a time that I challenged a practice that I found disturbing at the Department of Urban and Regional Planning of the University. It was the case then that during a propositional seminar, students were required to cook – usually pounded yam – for the lecturers and some students. It was not a written law but a tradition which had gone on unchallenged and had become more like a law. It was like a big ceremony. I felt strongly then that the practice was wrong, because many times the proposals were eventually deemed not in good shape at the seminar, and students were made to re-write or correct and represent at another seminar. It meant that some students cooked twice to present a proposal for a master’s degree research. As I said, this did not feel right to me.

One day, I stood up at the seminar to express how I felt. I said: “I have seen cases here in which students would have been working on a proposal for two sessions. The program is supposed to last for two sessions, but many at times, supervisors will not approve of one’s proposal for presentation until the second session is almost over. That’s what you are doing. I am talking about the pre-field seminar. So eventually, many people spend three sessions”. I also complained about the fact that many candidates after working for two years or more on a research topic, that is when it comes to the departmental seminar, and that is when it would be said that the topic is not researchable. Whereas there has been a supervisor who has been checking the work over the past years. So I suggested that there should be a committee that one submits topics to as soon as one gets into the programme, so that the committee can help confirm whether the topic is researchable or not. I also remember recommending that some older professors should be assigned as assistant supervisors. So that even if a professor is not chanced enough, the assistant can fill up the gap to ensure that students are not delayed. I made three recommendations. I also recommended that there should be training and retraining for both supervisors and students on how to conduct good research.

Well, all three recommendations didn’t meet the Professors well. Coupled with the fact that when I did my propositional seminar, and later my final oral seminar, I didn’t give them the usual pounded yam and all. I only gave meat pie to them. And of course, I’ve been telling my colleagues that this practice of having to provide pounded yam for lectures is wrong, and that we have to challenge it. Of course, some of them who are friends with lecturers told them. So when I did it, they knew that it was an act of resistance. So the need was an act of resistance, because the lecturers also knew that I had a small scholarship of about #350,000, which was a significant amount of money then. My school fees for the two sessions at that time was about #107,000 something. So they knew I had the money.

So, one professor approached me in 2016, Professor Abel Afon, a pastor, saying that “if I were you, I would not come back to this department, because, obviously, you can’t finish here”. He was talking about my PhD which I had just started. Hearing that, I went to the University of Ibadan (UI) to obtain another form. I submitted all the processes and kept it somewhere. By the time the studentship termination letter issued to me arrived months later, I simply went back to see whether I could still meet up with the program at UI. I had attended a few lectures and wrote the exams actually, even though I wasn’t sure what I was going to do with it. When, eventually, the studentship termination letter was issued, I just made-up my mind. I was not going back to the department at OAU. The decision was also influenced by the information I got that the same professor who had approached me, bragged to his students while in class, saying “you guys should better be good to us, because one of you was very rude, and I was called from the Postgraduate College to see what should be done to him, because he’s one of those who led the protest against the provost. And I said we’ve been trying to send him away.” A friend reported that to me that that was what the man said in class. So I just made up my mind that there was no reason to go back there, and I decided I was going to go face the programme at the University of Ibadan.

Blessing: Interesting, can you share more about the actions you have taken against injustice?

Gideon: I was active during the #EndSARS protest of 2020. If you’re if you were a young activist in Nigeria at that time, I am not sure it’s possible not to be active in the protest. I was always going out to help coordinate as much as possible, helping to articulate what people were saying. In 2021, I came from Ife to Lagos for the #EndSARSMemorial action. I was arrested alongside 32 or so others, I think 33 of us were eventually prosecuted. We appeared before the magistrate late at night, the same day we were arrested. The court sitting ended close to midnight, and the case was adjourned. I came back about a month or two later on the date that our case was adjourned, and the magistrate threw the case out because there was no evidence against us. We were charged for public disturbance, something like that. Of course, in between these actions, I have joined and mobilized for a number of other actions and campaigns, in workplaces and so forth.

There was a place where I worked, Lawal Educational and Islamic Foundation. The owner of the foundation was mistreating workers, and I had to mobilize the workers to challenge him. Of course I was sacked afterwards. Before the action, I had been worried and lodged a complaint about the way workers were being treated. The man would employ workers and two months after resuming there won’t be salary, and then he would come up with something the individual has done wrong before sacking her/him. So many left without getting two or more months’ salary. I saw it and I was worried, and then I challenged him. I mobilized many who had been sacked like that over the months preceding that time, and it became a big movement. And they got their owed salaries. So, there were actions like that. I think a report of that action is still on socialistnigeria.com. This year 2024, I have mobilized for the #EndBadGovernance and other actions.

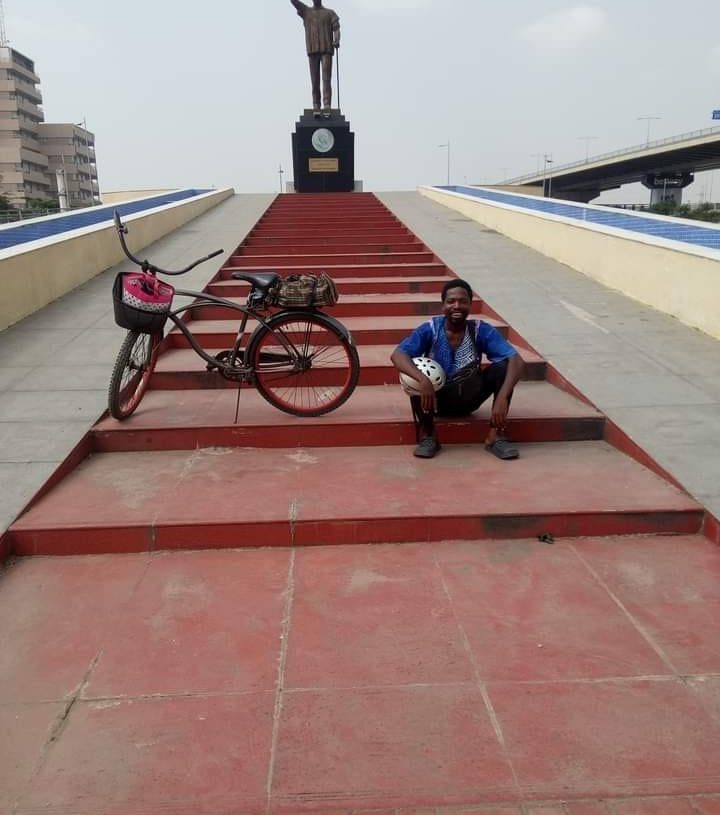

I should not forget to mention my involvement with Africans Rising (AR), which is a Pan-African movement, Last year December 2023, I rode to Ghana as a solo action in support of the AR campaign for free movement of Africans on the African continent. The campaign simply demands that Africans should not face the kind of ridiculous restrictions that we face in Europe while trying to move on the continent. So, I rode with a banner with the inscription “Break the Colonial Partitions”, saying that the partitions left by the colonialists many decades ago should be abolished. I agree that we shouldn’t still maintain something that serves the colonial agenda of dividing us so that we can be easily ruled.

Blessing: Thank you so much. Can you talk about your ride in support of the African Rising campaign for free movement? Was it fun, exciting, challenging?

Gideon: It was in 2022 that I suggested to the Africans Rising Core Team that we need what I call Pan-African Freedom Rides. This is to support people to physically transcend those partitions, move across them, whether by walking, driving, riding et cetera. To support people in any way to move across those partitions and experience the other sides. I realized that many people within those borders have never really moved beyond them. I suggested the action, which I called the Pan-African Freedom Ride. So that when folks move across these partitions, they can also psychologically transcend them, to see them as arbitrary, as superficial, as unreal. In 2023, I was able to go on the first ride, which I call a pilot ride, as it was meant to inspire others to do the same. So, what I did was a bicycle ride from Lagos, Nigeria to Accra, Ghana. It took me 6 days. Of course, the first major challenge was the effect of long hours of ride on the body. I became weak after the first two days, very weak. My legs became very heavy. But of course, I kept on going.

The human body, I came to learn, has a way of adapting to many situations. And I think that’s one of the things that I learnt during the trip. Human capacity is so enormous. Our body can adapt to situations that we cannot imagine that it can adapt to. Our body can do things that we do not even know it can. The ride was just a very rigorous and energy-consuming exercise. There was a time that I missed my way in Togo. I think I became overconfident of my knowledge of geography. What I had been doing was to ask passersby and check my map. But at that point, I felt so sure of myself that I wasn’t asking anyone for the way. And then I got lost and I had to ride for many hours to get back on the main road. That was a challenge that I faced. There was also the challenge of uh, I almost had my tablet, which was always in a cross bag that I had with me, stolen. That happened at the Aflao border in Ghana.

But generally, people were very kind to me. When I tell the story of what I was doing, especially to young people I met on the way, they were excited. And many of them felt that it was a worthwhile adventure. The people that I met, and the interactions I had with them, made the trip more memorable for me. I should also mention that the scenery that I saw, the landscapes, were just beautiful sights. So that was also enjoyable. I remember there was a point that I was riding alone on the highway, everywhere was quiet and I just screamed, because I was very excited by the scenery around me.

A journalist-friend once asked if I wasn’t afraid of kidnapping and all. And I jokingly said that I think I looked like any other poor person who was riding to the farm. I had very small items. What else? I had Garri and dates in my basket. So, l think I looked like any other ordinary person. I didn’t feel any threat.

I had a small bag in my basket in front of the bicycle. I eat garri once in a while when I feel like, I eat other foods, roadside food, whatever that could pass for a vegan option, on my way.

Blessing: What are the actions that you think have made the most impact in your activism?

Gideon: It’s difficult to tell the magnitude of the impact of our actions, and I think that’s also a challenge with what we do. Like the action that I took to stop the practice of lecturers demanding food from students during seminars at the Department of Urban and Regional Planning, Obafemi Awolowo University, I was told by a friend many months after I had left the university that they’ve stopped the practice. Maybe it is connected to my action. But sometimes you cannot easily tell. One cannot say that it was because of a singular action. It’s possible somebody else did carry out other actions as part of the campaign.

If we look at the ride to Ghana, quite a number of people have said they want to do the same thing. I’ve seen folks say stuff like “it is true that the decolonization of Africa is not over”, in response to that action. I saw someone put up an article somewhere, referencing and commending the action. So, I think a lot of people have also become more aware of the need to continue to advance the decolonization agenda in Africa, following that action.

I also remember the Lekki Toll Gate action for which I was prosecuted in 2021. The government was trying to say then that nobody was allowed to protest at the Lekki Toll Gate. And the reason I went back there with some other folks was to say that ‘we can protest anywhere…those in government cannot decide where to exercise this democratic right.’ People have been going back there for action afterwards. Maybe this is connected to some of us going back there in 2021.

In terms of changing a law at the government level, I can’t remember anyone right now. But I feel of course we must have created some impact that maybe we are not able to track for now. Albert Einstein once said not everything that counts can be counted, and not everything that can be counted counts. So, I think that sometimes very impactful actions lead to impact that it may not be able to put metrics on. It doesn’t mean that our actions are not yielding impact on society.

Blessing: Have you ever been deterred as a result of impact not happening at the rate at which you want it?

Gideon: I recognize that the struggle to transform society is a marathon. It’s not a Sprint that one arrives at one’s destination in a short while. Oftentimes it doesn’t happen that way in environmental and social justice struggles. Like the trip to Ghana, the action is part of a long-term campaign. The action must have helped galvanise more support towards the campaign.

On the question of whether I get tired sometimes. Well, I cannot deny the fact that there are moments when one feels overwhelmed by the magnitude of the challenges that we face. I mean the extent of work that has to be done, the work of conscientization that has to be done.

Sometimes I am bothered by how those who are oppressed by the systems that we confront defend the same systems. So one sees oppressed people condemn resistance actions. Fighting patriarchy, for instance, one would realize that there are women who will challenge resistance actions against the system. So, like the colonial partitions as another instance. One will see very poor folks – whose poverty is not unconnected to the economic havoc being wrecked by the existence of these partitions, which prevent the free flow of goods, services and people – argue that what we need is to create our tribal nations, to even increase the borders; not to break them. So, there are times when one hears and sees these kinds of things and it breaks one’s heart.

But of course, like I said earlier, we have to recognize that the struggle is a marathon. We have to keep fighting. We cannot afford to become hopeless; and to submit to the pessimism that nothing good can come out of our actions. Because history tells us otherwise. History tells us that when people act courageously, and with clarity, with clear vision of just society, their actions always bring change in society. So, I’m always reminded of this lesson of history, telling us about the justification and need for hope. Sometimes when I face certain challenges and when I am glaringly reminded of the magnitude of the work that remains undone in terms of mobilizing a critical mass of our people for resistance, I get weighed down. But It doesn’t last. I’m usually reminded after a short while that we have to keep fighting.

Blessing: Amazing. That’s good. A punch line I have from that is “the struggle for justice is not a sprint; it’s a marathon”. Lastly, what inspired your physical look?

Gideon: For me, I agree that the mind is a standard of the human. By this it is implied that the human should be assessed based on the content of the character, the kind of ideas that the individual is committed to propagating, how much the individual is committed to the realization of eternal ideals of freedom, justice and peace. So, I think that is the right way to assess humans. What is seen in our world is that there is so much emphasis on how individuals look. You know the idea of ableism, in which people who have bodily impairments are considered to be inferior to others. There is also the idea of colourism, in which people of light skin tones are privileged over people with dark skin tones. One would easily recall a traditional ruler in Yoruba land who had a number of wives and all of them were light-complexioned. I am talking about the last Alafin of Oyo. It was because of that colourism. So, I think it’s It’s been misguided. I think it’s a sort of disorientation to place so much emphasis on how we look, how we appear than we do on what is the content of our minds. So, personally, I don’t place so much emphasis on it. I just want to do a minimum that will not make many people think that this guy is crazy. Once I have done that very minimum, I’m just fine.

I also try to use materials that are easy to maintain. As for my hair, I’m not just comfortable going to the barber every now and then or having to shave my beard very often. Luckily for me, some people think I’m trying to look like Wole Soyinka while some others think it is Karl Marx. So, I get a sense that my look is still within a range of what is minimally acceptable in the society. The minimum acceptable standard of appearance is what I just go for. It’s part of my minimalist orientation. Yes, I am a minimalist.

Blessing: Thank you so much. That would be all from me. Is there anything you would like to talk about that I’ve not asked?

Gideon: I think I should just add that I believe that we can have a better world, we can have a more just world. It is not utopian thinking to think that we can have a world where not a single person goes to bed hungry or will be homeless. I dream of that kind of world, and I know it is realizable. I’m hopeful that we’ll achieve it. Thank you.

Blessing: Thank you so much for your time.

Gideon: It’s a pleasure.