A report by the Disability Not A Barrier Initiative (DINABI) has laid bare the persistent marginalization of persons with disabilities (PWDs) in Southwest Nigeria, showing that the region’s 2025 state budgets treat disability inclusion as little more than an afterthought.

When the states’ governors presented their 2025 budgets, they spoke expansively about economic growth, infrastructure renewal, social protection and human capital development. But buried beneath the trillions of naira allocated to roads, security, education and health is a quieter story, one that concerns millions of Nigerians living with disabilities and how little space they occupy in public finance planning.

Data from the ThisAbility Budget (TAB) platform, developed by DINABI with support from The Disability Rights Fund (DRF), offers a rare, evidence-driven look into this gap. The platform compiles and analyses disability-specific budget lines across Ekiti, Lagos, Ogun, Ondo, Osun and Oyo states, showing not only how much each state plans to spend in 2025, but how much of that spending is explicitly directed at persons with disabilities.

Rather than broad social welfare figures or aggregated “vulnerable groups” spending, the data focuses strictly on disability-specific allocations, funds clearly earmarked for disability agencies, programmes, assistive services, inclusion initiatives or legal mandates related to persons with disabilities.

Across the six Southwest states, TAB’s analysis shows that disability-specific allocations form an extremely small fraction of total 2025 budgets, even in states with established disability laws or agencies. In practical terms, this means that while states may reference inclusion rhetorically, the budgets that determine policy priorities tell a different story.

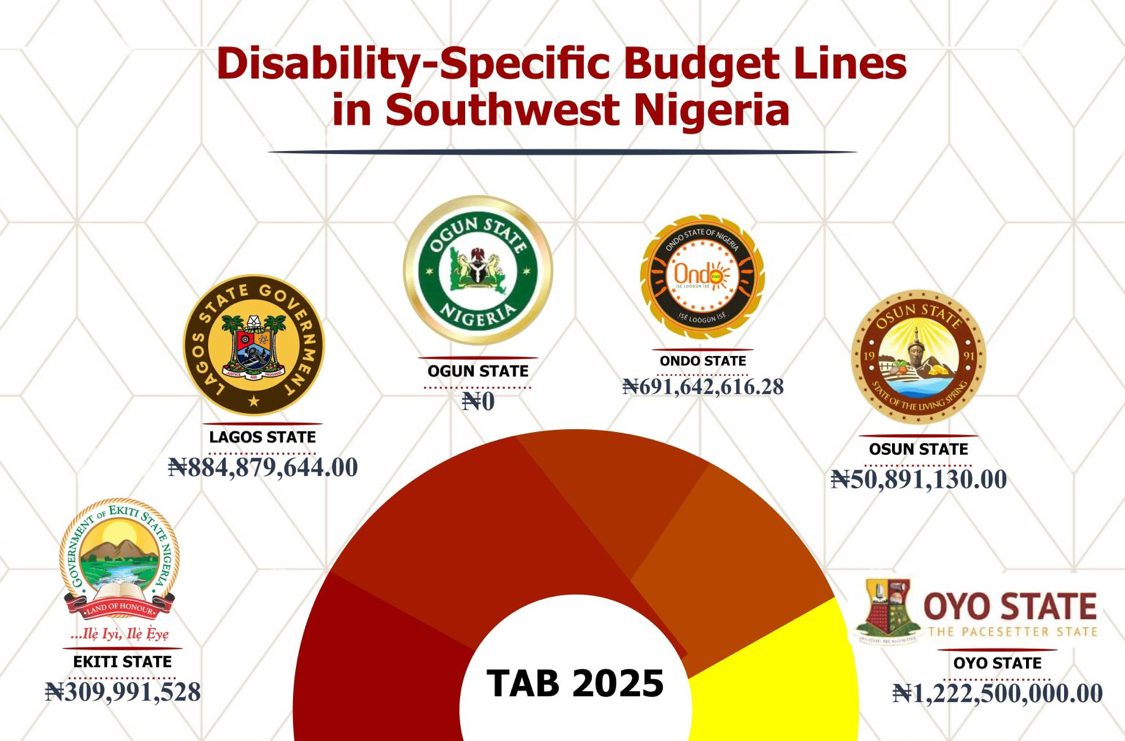

Oyo State recorded the highest disability-specific budgetary allocation for 2025, approximately ₦1.22 billion, representing about 0.18 percent of its total budget. Although this is the largest share in the region, it still falls decades short of what disability rights advocates argue is needed to guarantee inclusion and compliance with legal and international standards.

The TAB data shows that Lagos State, with one of the largest total budgets in the region, allocated an amount that represents roughly 0.026 percent of its 2025 budget to disability inclusion. This is despite the presence of a dedicated Office of Disability Affairs and prior allocations recorded in state budget summaries.

In Ekiti, Ondo, and Osun states, disability allocations were similarly meagre, rendering PWDs a low priority in fiscal planning. Ogun State stood out for its complete lack of identifiable disability-specific line items in the 2025 budget, indicating zero direct funding for disability inclusion activities or agencies.

This widespread underfunding persists even though all six states have relevant laws or commissions purportedly meant to protect disability rights, showing that legislation alone is insufficient without corresponding budgetary commitment.

Why Disability-Specific Budget Data Changes the Accountability Conversation

The significance of TAB’s data lies in its precision. By isolating disability-specific budget lines, the platform removes ambiguity from public finance debates. Governments can no longer rely on vague claims that persons with disabilities are “captured” under general social spending. The data asks a direct question: how much money is actually set aside for disability, and how does that compare to the size of the budget and the population affected?

This approach fundamentally shifts accountability. Budgets are not neutral documents; they are expressions of political choice. When disability allocations consistently fall below one percent of total spending, it signals that inclusion is not a governing priority, regardless of existing laws or public commitments. For persons with disabilities and civil society organisations, TAB’s data provides concrete evidence to challenge these choices, engage lawmakers, and track progress — or the lack of it — over time.

The platform also exposes structural weaknesses in budget transparency itself. Many disability stakeholders remain excluded from budget processes because documents are inaccessible, overly technical, or released without meaningful consultation. TAB bridges this gap by translating complex fiscal data into interpretable insights, allowing disability advocates to participate in budget discourse on equal footing.

In a region where disability laws exist but enforcement is weak, this kind of data becomes a powerful accountability tool. It connects legal rights to financial reality and makes it possible to ask whether states are funding their obligations or merely acknowledging them on paper.

Innovation Beyond Numbers: Why TAB Matters

Beyond the figures, TAB represents a methodological innovation in Nigeria’s civic and data ecosystem. Disability-focused budget tracking at the subnational level remains rare, and even rarer is a platform that presents comparative data across multiple states using a consistent framework. By doing so, TAB enables trend analysis, peer comparison and regional advocacy, allowing stakeholders to see which states are improving, stagnating or regressing.

More importantly, the platform reframes disability inclusion as a governance issue, not a charitable concern. By grounding advocacy in budget data, it positions persons with disabilities as rights holders entitled to public resources, rather than passive beneficiaries of goodwill. This shift is crucial in a country where disability is often discussed in moral or humanitarian terms but excluded from economic planning.

The data on TAB also creates opportunities for journalists, researchers and policymakers to interrogate broader questions: how inclusive development is measured, how budget priorities reflect social values, and how marginalised groups are systematically deprioritised through fiscal decisions. In this sense, the platform does not merely report numbers; it invites scrutiny of the political economy of inclusion.

The 2025 budget data captured on the ThisAbility Budget platform tells a consistent story across Southwest Nigeria: disability inclusion remains peripheral in public spending, despite legal frameworks and public commitments. While variations exist among states, the overarching pattern is one of minimal allocation, weak prioritisation and limited accountability.

Yet by making this data visible, comparable and accessible, TAB introduces a new dynamic into disability advocacy. It transforms budgets from closed government documents into public accountability tools and offers persons with disabilities a factual basis to demand better governance. Whether states respond with meaningful reforms or continue with symbolic inclusion will be reflected not in speeches, but in future budget lines, and TAB has ensured that those lines can no longer go unnoticed.