According to a UNICEF report from 2016, six out of every ten children in Nigeria suffer some type of violence before the age of 18. The report also says one in every four girls and one in every six boys are victims of sexual violence.

In 2021, in one of the communities in the Federal Capital Territory, a 14 years old Abigail was raped by Mr Ahmed a 45-year-old who was a friend to her father.

Abigail was raped in Mr Ahmad’s house when she visited him upon his invitation. Mr Ahmad had invited the teenager to his house with the promise of giving her a gift.

Abigail had narrated the story to her father, Mr Hassan on getting home who had, in turn, reported the case to the police.

Abigail’s story is just one of several stories of children who have become victims of SGBV in the Federal Capital Territory.

The National Human Rights Commission, NHRC, through its executive secretary said it recorded a total of 4,000 complaint calls from victims of sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV) within nine months in 2021.

Although feminist activism has worked tirelessly over the years to combat violence against women (VAW), progress has been slow, especially given the severity of VAW in Nigeria.

Cultural customs, norms, and behaviour such as acceptance of violence as a personal affair within the family, stigmatisation, assumed superiority of the make child, economic disempowerment of women among others that have been strongly ingrained in most local communities have been identified as a significant impediment.

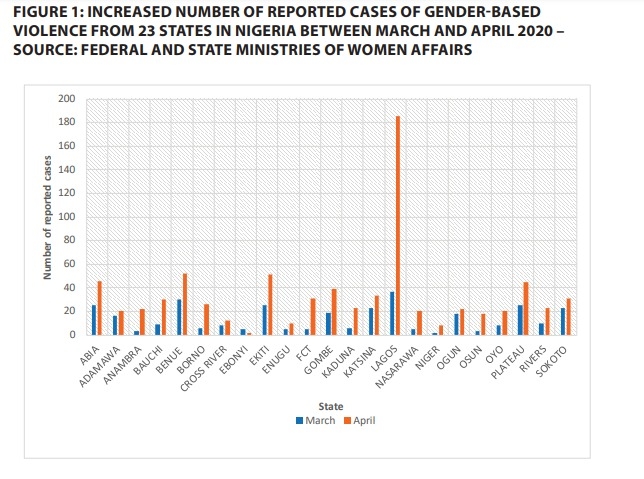

More importantly, the pandemic has further increased the likelihood and prevalence of SGBV as a result of the lockdown, and its accompanying effects. This has downplayed the impact of previous efforts to eradicate gender-based violence (GBV) in the country.

A joint research published on the UN Women website holds that there has been a spike in the reports of abuse such as intimate partner violence and domestic and sexual abuse of women and girls under lockdowns.

The UN also reported a significant increase in GBV since the lockdown with the three most affected areas being Lagos State, Ogun State and the Federal Capital Territory in 2020.

In rural places, where essential services such as hospitals, support centres, and the police are out of reach, many more cases of rape and sexual crimes go unrecorded, unheard, and unreported.

This current situation necessitates concern and the development of the best available solutions, which may necessarily include the participation of rural communities.

According to the UN’s deputy secretary-general, Amina Mohammed during the launch of the WithHer Fund in 2021, stated that “Civil society and grassroots organisations are the keys to transformative and sustained change,” according to the UN’s deputy secretary-general.

Organizations such as the UNHCR have used community engagement to prevent and respond to SGBV.

The responsibility of fighting SGBV must importantly include the rural communities, Aisha Yusufu, the gender desk officer at the Abuja Municipal Area Council, corroborated this. She explained that the government cannot solely fight against SGBV but rather involve non-governmental organizations who are well-positioned to create awareness and sensitize community leaders on how to manage cases of sexual abuse and prevent it.

In the Federal Capital Territory, the SOAR (Sexual Offences Awareness and Victims Rehabilitation ) initiative is one of the NGOs leading the fight against SGBV and changing the narrative on how communities perceive and respond to Sexual and Gender-Based Violence (SGBV) against girls in the community through its coordinated community response system.

In the heat of the pandemic in 2020, the organisation launched another phase of its grassroots intervention program on ‘Sexual and Gender-Based Violence’ with support from Rule of Law and Anti-Corruption (RoLAC) to benefit girls who are victims of SGBV and protect more girls from being victims.

This was launched in four communities in the Federal Capital Territory: Tasha1 and Wukara in Abuja Municipal Area Council, Kayarda in Kuje Area Council and Wuna in Gwagwalada Area Council.

Chineye Enoh, the executive director of SOAR Initiative, said the project was designed for community members ‘ to recognise sexual abuse against children as a human rights violation and not just an issue to be settled at home.’ The UNHRC has defined Sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV) as any act that is perpetrated against a person’s will and is based on gender norms and unequal power relationships. It includes physical, emotional or psychological and sexual violence and denial of resources or access to services.

In each of these communities, the organisation constitutes a Community Child Protection Committee (CCPC) who are trained by SOAR on preventing Sexual & Gender-Based Violence and effective case management of SGBV cases which especially include protection and prosecution.

In total, 110 CPCC members have been empowered and inaugurated in the four communities included. The peer educators program has enrolled 1194 children, with 32 peer educators being taught to prevent, identify, and respond to situations of girl child sexual abuse

The CCPC is a group of community members entrusted with keeping track of rape and sexual offences, investigating them, and reporting them to the appropriate authorities. The team members are chosen based on volunteerism and community approval; the team, in particular, includes people living with disabilities.

Girls and young women with disabilities face up to ten times more gender-based violence than those without disabilities, according to a UNFPA report. Furthermore, children with disabilities are approximately three times as likely as children without disabilities to be victims of violence and sexually molested, with females being the most susceptible. In a study by the African Child Policy Forum most children living with disabilities have been sexually abused, and the majority had been sexually abused more than once.

Hafsar Ishau, a CCPC member in the Kayarda village who lives with a disability, explained that the unique challenges of girls living with disabilities make them more vulnerable to abuse.

These unique challenges include lack of shelter for some, disability in physical sensory which could help them detect the presence of an abuser in time.

In addition to the CCPC, another element of the project focuses on training children and parents to recognize SGBV and abusers, thereby preventing or minimizing the likelihood of recurrence.

According to Usman Dalatu, one of the Wukara community’s mentors, “It is impossible to teach a child without also educating the parent. Parents and children must be educated on the rights and boundaries of interaction “.

As a result, a peer educator training program for girls in all schools has been implemented to educate them on how to prevent and defend themselves from SGBV.

Lydia Hassan, one of the teenagers that was sensitized shared that “I have learnt that sexual abuse is an offence, and the mentorship has made me know my left from my right when it comes to sexual abuse”.

Parents are also given ongoing training on how to safeguard their children and seek justice if they are harmed.

The World Bank opines that reducing SGBV must involve multiple stakeholders which essentially includes the girls and their caregivers.

The Situation before the Project

“Sexual abuse is so rampant, that girls in primary schools are already abused by men. Some can’t even stay in their father’s house because of men and because of that cannot further their education” Obinna Orji, the Wukara mentorship coordinator who has lived in the neighbourhood for almost 9 years, expressed himself in these words.

Obinna went on to say that some of the victims in the village were married off to the perpetrator.

The secretary of the CCPC in Wuna Community explained that the community King and his cabinet were in charge of deciding penalties for SGBV cases reported in the community; however, there is sometimes a relationship between the perpetrator and one of the cabinet members, which leads to a tendency for justice to be compromised.

The secretary, Ibrahim said that children were also not able to decipher the tricks of perpetrators which eventually lead to sexual abuse.

For instance, is the case of Comfort, a junior secondary school student, who has been receiving some gifts from an older man in the community. She said that the man had told her he loves her.

It was during one of the mentorship education programs in Comfort’s school that she opened up to one of the mentors. Comfort had informed the mentor that she didn’t want her parents to know, but promised the mentor she would stop receiving the gifts having learnt that it was one of the tricks employed by perpetrators.

“I am afraid of what my parents would do, so I didn’t want to tell them”.

It had required some persuasion by the CCPC for Comfort to inform her parents.

The CCPC had visited her parents to discuss how Comfort can be protected from exploitation and any potential sexual abuse. During the interview, the mentor, Ali said “It is important for parents to be free with their children. This will make them know when their children are in danger or close to it”

Tracking Result

In the Wuna community, Maman Alina (not the child’s real name) a 14-year-old teenager had summoned the courage to write to the CCPC after attending a series of sensitization in the community. The CPCC has established the report of SGBV to be written, to encourage females to safely express themselves.

Alina’s story started in 2019 when she was just eleven years old. “I fear to tell anybody” Alina had tolerated the sexual abuse of Tajudeen Bako(not his real name) who was already over 50 years as when he started abusing Alina.

The CCPC had reported the case to SOAR , who had worked with the police and NAPTIP to ensure justice is served.

Though Tajudeen was arrested initially, he is presently back in the community. The CCPC informed that SOAR has assured them that the case will be monitored and investigations are ongoing.

Usman stated that early adolescent pregnancy has decreased in the Wukara community and that pregnant teenagers are being returned to school following birth. Though in the case of Rebecca Jeremiah and Hannatu Sani (not their real names), they have opted to learn a skill rather than continue with their education.

“Partnership is one of our working strategies,” said Yakubu Levi, the project officer. It has become easier to work and achieve results in the community as a result of this.

For example, the organization has collaborated with existing structures throughout the area councils, such as the social welfare and gender response desk officers, to better understand the context of each community and gain support for the CCPC. It also worked with important stakeholders in each community, such as religious and traditional leaders, and coordinated with the National Agency for the Prohibition of Trafficking in Persons (NAPTIP).

Magnus Ameh, the head of NAPTIP’s response team, said the organization’s passion was a driving force behind its support for SOAR, especially given its legal restrictions on executing SGBV legislation. He also describes their efforts as complementary, recognizing that the Agency cannot be everywhere at all times. During the lockdown, he claims, “cases were received on a regular basis,” and that following investigation, he learned that these instances were received during the organization’s grassroots sensitization effort.

Strengthening the System

Despite the project’s and its approach’s success, there have been reports of obstacles in the implementation process.

“Our work is similar to that of police officers, and you know a police officer is never a friend to a thief,” Ibrahim said, adding that culprits in the community, particularly when they are close friends, have viewed them as adversaries.

Usman also informed that there are still situations that have not been handled since the victim’s family has refused to allow them to intervene. “Those cases are still there, even if we’ve made progress.” He told the story of a young girl who had recently been assaulted, but the mother argued that the alleged culprit was well-known and could never harm her daughter. To escape further inquiry on the matter, the woman eventually fled the town without disclosing to anyone she could be traced to.

According to gender activist Dami Ogunsakin (Esq.), incidents like this are not uncommon, but it is critical that parents are continually educated on the short and long-term effects of SGBV on their children.

Furthermore, the considerable time it takes to get justice for victims of SGBV with the Nigerian judicial system can thwart the quest for justice.

For instance, in the case of Alina, which has been ongoing since 2021 and whose perpetrator has not been convicted.

Cynthia Ibe (Esq.), a response service provider with the International Federation of Female Lawyers (FIDA) said it usually takes a year to get a conviction for SGBV cases or even longer. She expressed that “With legal frameworks such as the VAPP act, one would expect the conviction of SGBV cases would be faster, we are really lagging with implementation of our laws and justice process in the country”.

In 2021, the desk officer of the response team for sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV), federal capital territory (FCT), Ngozi Ike, revealed that out of 444 SGBV cases reported in the city, only one conviction was made.

Cynthia suggested that the judicial proceedings on SGBV cases should be reviewed to fasten the process of delivering justice to survivors.

The UNODC also reported that cases of SGBV are the least likely to end in conviction.

In the community, the CPCC secretary said that money is usually a challenge for the committee, and even though the committee has devised a system to raise cash from within the community to solve this, there is still a deficit in the needed financial resources to manage cases some times. Some community members have requested money, according to Bar Oladayo, another SOAR project officer, and it has been noted that the enthusiasm level of some of the members who were initially enthusiastic has fallen as they realize there are no financial benefits. On the other hand, we are recording impacts with other members, who are still deeply committed to the cause.

Sustainability

A community-based response system must have a long-term sustainability plan, otherwise, the impact will be short-lived. One of the ways SOAR’s grassroots intervention program is striving to assure sustainability is by establishing a local system that can track sexual abuse, prevent it, and break the culture of silence on its own. “We want the members of the committee to constantly uphold their values and remain objective in monitoring and reporting incidents even after we leave,” Yakubu says. Though we will continue to assist them through our Child and Adolescent Support Program.”

The child and teen support centre is designed to provide comprehensive medical treatment and psychosocial therapy to survivors of rape and sexual violence. According to Mercy Nwanchukwu, each reported case at the centre begins with biodata documentation, which includes an appraisal of the case for management or referral, as well as the type of treatment necessary. The Teen and Child Support Center has received over 300 calls and handled over 90 cases since its start.

Going forward, to have an optimum impact, it is critical to enlist community members in the fight against sexual abuse against girls at the grassroots level.

It is also critical for more intervention that creates and implements locally coordinated community response systems in order to replicate impacts in more communities and therefore accelerate the process to ending SGBV.

This article was produced with the support of the Africa Women’s Journalism Project (AWJP) in partnership with the International Center for Journalists (ICFJ) and through the support of the Ford Foundation.