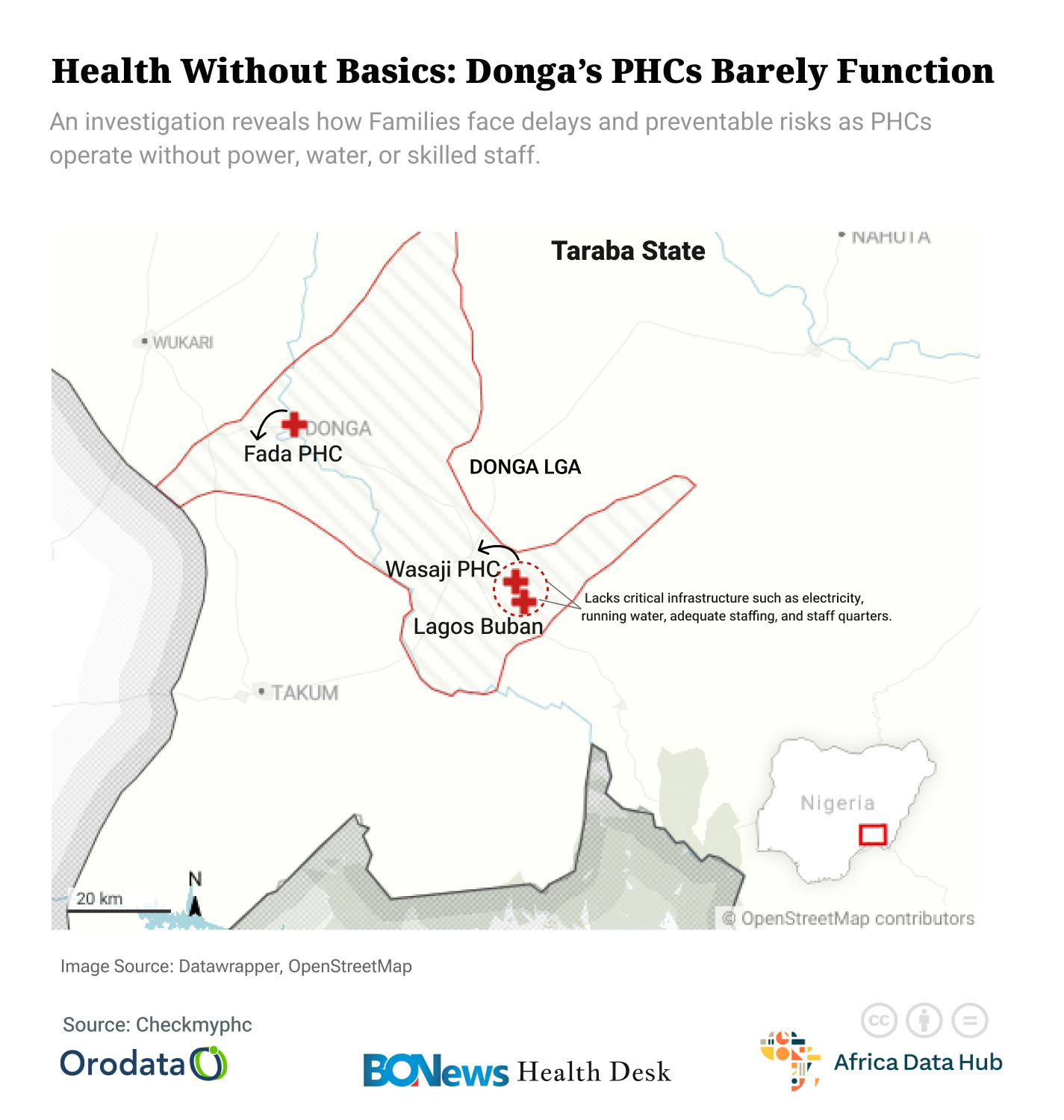

In the Donga Local Government Area (LGA) of Taraba State, Primary Health Centres (PHCs) and health posts meant to serve over 150,000 residents are operating without basic infrastructure and amenities. Data from Orodata’s CheckMyPHC platform and the National Primary Health Care Development Agency (NPHCDA) reveal that facilities such as the Wasaji Health Post, Lagos Buban Health Post, and Fada Primary Health Clinic lack essential amenities. This situation undermines healthcare delivery in the communities they serve and erodes public trust and confidence in the system.

The World Health Organisation emphasises that the primary health care approach is to effectively organise and strengthen national health systems, bringing essential services for health and wellbeing closer to communities. This system supports people’s diverse health needs, including health promotion, disease prevention, treatment, rehabilitation, and palliative care, while ensuring that health care is delivered in a way that is centred on people’s needs and respects their preferences.

In Nigeria, PHCs and health posts have the mandate of providing antenatal care, labour and delivery, routine immunisation, treatment of children with cough, fever, and diarrhoea, and other community health services. The commitment of the Nigeria Health Sector Renewal Investment Initiative (NHSRII) and NPHCDA’s Sector-Wide Approach (SWAp) to revitalise PHC facilities and expand to about 17,000 PHCs in a span of 4 years underlines the national importance of primary health care. Yet, for many residents of the Donga LGA, the nearest health centre is just a building with minimal essentials that make quality healthcare possible.

However, data from Orodata’s CheckMyPHC platform reveal a troubling gap between these commitments and the actual state of primary health care delivery in Donga LGA. Records show that the Wasaji Health Post, Lagos Buban Health Post, and Fada Primary Health Clinic are among several facilities that lack critical infrastructure such as electricity, running water, adequate staffing, and staff quarters.

At the Wasaji Health Post, there is no form of security, including security personnel, perimeter fence, or perimeter gate. Although the facility has one delivery room and one consulting room, they are both in poor condition and under-equipped. Also, the facility has no ambulance service and transportation for referrals to other health facilities is arranged by the patients in private vehicles during emergencies. CheckMyPHC data also revealed that the facility has no power source, toilets, or water source, with patients and staff relying on the village borehole and the stream for water. Facility waste is disposed of via pit burning, which poses environmental and health risks.

This reality is corroborated by data from the NPHCDA website, which notes that while the facility requires at least four Skilled Birth Attendants (SBAs) to function effectively, it currently has none. Instead, the CheckMyPHC data shows that the facility only has one Community Health Extension Worker (CHEW) providing healthcare services to patients.

CheckMyPHC records that at the Lagos Buban health post, the building is not properly structured or maintained, and although the facility has a perimeter fence, it has no gate or security personnel, which points to inadequate security for both staff and patients. The facility also does not operate for 24 hours, indicating that residents of the community lack healthcare access during emergencies at certain hours of the day. The facility has no ambulance service, with patients relying on motorcycles for referral transportation during medical emergencies.

Although the facility relies on a borehole for water, it lacks a power source, with staff and patients relying on torchlights for power. Records from the NPHCDA website show that the Lagos Buban Health Post has no delivery room, with CheckMyPHC corroborating that the facility has no wards. Also, NPHCDA records that although the facility requires at least four Skilled Birth Attendants (SBAs) to be functional, it has none. A statement emphasised by CheckMyPHC that the facility has only one Junior Community Health Extension Worker (JCHEW) working on the facility.

At the Fada Primary Health Clinic, the reality is just slightly different from what is obtainable at the Wasaji and Lagos Buban Health Posts. CheckMyPHC records that while the facility has a well-built and maintained structure, it lacks a perimeter fence and gate, which points to an obvious lack of security for stakeholders in the facility. The facility also has no ambulance service, with patients relying on motorcycles for transportation during referrals and emergencies.

The facility relies on a borehole for water, while power is provided by torchlight, and facility waste is thrown into a pit dug in the compound. While CheckMyPHC records that the Fada Primary Health Clinic currently has four Community Health Extension Workers (CHEW) operating in the facility, the NPHCDA records indicate that the facility needs two SBAs to function; it currently has none.

Across these three facilities, the data highlights that health centres in the Donga LGA operate under subpar conditions that make effective service delivery nearly impossible. For the residents of the LGA, this reality translates into delayed care, preventable complications, and a deepening distrust in the public health system.

These data reveal the lived realities of mothers, children, and families whose health outcomes reflect the absence of basic health amenities. This crisis exposes a gap in effective service delivery that endangers lives and erodes public confidence in the health system, especially when these facilities are close to schools and a community palace.

The lack of power, manpower, and essential equipment means that available health personnel will find it difficult to deliver safe and timely care. Without electricity, birth deliveries and emergency procedures are referred to other health facilities, which may pose serious challenges to the survival of mother and child, given the lack of ambulance services in these facilities.

For pregnant women, the lack of functional delivery rooms or SBAs often means seeking out maternal care in other communities, which might prove a great risk for mother and child, especially when this commute is mostly done using motorcycles. Although the facilities provide immunisation services, this could be disrupted due to the lack of power in these facilities. These gaps point to a lack of public trust in the primary healthcare system, a situation that can be mitigated by stronger oversight, equitable funding, and genuine commitment to the revitalisation of rural health facilities.

Despite existing government initiatives like the Primary Health Care Revitalisation Agenda and the Basic Health Care Provision Fund (BHCPF), the reality in Donga LGA suggests that these interventions have not been evenly implemented. Persistent gaps in supervision, transparency, and equitable resource allocation continue to undermine the promise of quality healthcare at the grassroots.

However, open-data tools such as Orodata’s CheckMyPHC platform and the NPHCDA dashboard now serve as a mirror of accountability, revealing not only the gaps in infrastructure and staffing but also the human cost of neglect.

This story was produced by the BONews Health Desk, supported by the Africa Data Hub and Orodata Science.