Dear readers,

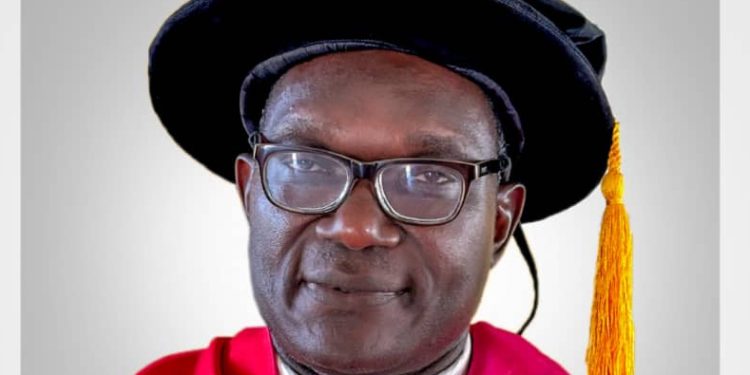

I am excited to present the first issue of the Disability Champions Series for 2025. In this issue, the 23rd, we bring you the riveting “pressing on to higher grounds” story of a Deaf academic at one of Nigeria’s most illustrious institution of special education. But he doesn’t get dizzied by the heights. Rather, he measures achievement by “wines poured forth” as he flashes back the challenging path leading to the present. Meet Dr. Adebayo Adekunle Akinola, (aka Triple A) a bright mind and achiever on the academic turf. In this interview with Alexander Ogheneruemu, he shares his story of living with deafness in measured doses of philosophy and humor – yes, and with insights for the disability narrative.

Background, growing up, becoming deaf

I was born on 27th July, over four decades ago. It was a memorable experience. The love from my parents, family members, teachers, etc, remains engraved in my heart. I was the second of five children. My late dad was a renowned architect, working with the ministry of lands and housing in Abeokuta, Ogun state. My late mom was a trader. She instilled values of hard-work, honesty and contentment in us from a young age. This prepared me for life’s storms.

Bayo became deaf under adventitious circumstances – the exact cause of which he’s unable to pinpoint. He gives a wistful snippet of the before times:

“I never thought this would happen to me. Being a jovial fellow, I had very fun-filled growing up years. At the hearing schools I attended right up to secondary level (St. Peter’s Anglican Primary School, Akesan; Rev. Kuti Memorial Grammar School, Isabo – both in Abeokuta), I was the life of the party – a mischief maker whose monkey business my fellow students enjoyed.”

Then it happened.

In his final year of senior high school, at seventeen or thereabouts, one evening, while preparing for evening class, he developed a headache and was taken to General Hospital, Sokenu, Abeokuta.

“The doctor gave me drugs. That night, I couldn’t sleep as the ache became unbearable. From then on I gradually lost my ability to hear. I missed words. In school, I moved to the front of the class so I could lip-read my teachers. It was a devastating blow. But I managed through secondary school and sat for SSCE.”

Home-bound and the search for cure

Experiencing deafness out of the blues meant this once a social butterfly could no longer participate as he was wont to in the funs of public life. As the sounds faded off his ears, Bayo became withdrawn, enveloped in melancholic discouragement. He recalls how home, once characterized by harmony and fun dissipated into bitter hate. With these came the why questions: “Why me? Why not my siblings?”

“I became irritated at everything, fomenting trouble and beating up whoever dared question my actions.”

Meanwhile, the news of Bayo’s deafness, borne on the wings of his popularity across schools in Abeokuta, spread like wild-fire – inflicting yet deeper, the pangs of pain and shame.

“I stopped school temporarily. With encouragement however, I returned and completed my secondary education. But for four years afterwards I was stagnated at home,” he recalls.

Luckily for him, a rare display of solidarity from a few friends and significant others at this critical moment came in strong for the distraught young man.

“They poured to our house, encouraging and begging me to return to school. Mrs. Adu (now Dr. Adu) my favorite teacher and Chief Bunni Fashola, my then Principal, really did their best in encouraging me. I can never forget them. I always thank God I listened to them.”

Even so, Bayo’s parents did all they could to get back his hearing but the ears simply refused to comply. When orthodox medicine failed, the search moved toward miraculous means. Yet, the several visits to churches, traditional healers, alfas (muslim clerics) all failed.

Riskat Robiu: The unlikely miracle of 1999

If you had told this champion the miracle he craved would come in the manner it did, he wouldn’t have believed for it came in the most unlikeliest of package. But Bayo, during a friendly chat leading to this series, demonstrated a sacred reverence for the individual and associations at the core of that miracle. Sometime in mid-1999, a cousin of Bayo’s, attending a muslim camp in Lagos saw for the first time Deaf participants included in communication through sign language interpretation. Curious, he asked questions and got to know about the Federal College of Education (Special), FCES, Oyo – one of the first tertiary institutions for special needs education in Nigeria and very strategic to the habilitation and rehabilitation of the deaf in Nigeria. He brought the news home.

Bayo narrates the outcome of that fortuitous encounter:

“One Sunday evening, I went to see my aunt. Unbeknownst to me, it has been pre-arranged that a Deaf lady (Riskat Robiu) who was one of those at the muslim camp would meet me there. She was told about me but initially didn’t believe I was deaf because I lip-read pretty well. She signed to me while I stared at her – angry. Riskat sincerely believed that the setting at the Federal College of Education (special) would greatly help my adaption and transformation. She had come to persuade me to come there. When I got to know her reason for coming, I got angrier. I made it clear I could never go to a school like that – insisting rather on the more prestigious university of Ibadan. But after a lengthy discussion in which I saw reasons Riskat really wanted me to go to FCES, I gave in. We went to see my dad and the following day traveled to Oyo. Going to FCES, Oyo marked the beginning of my adjustment to living with deafness and an upward swing in personal growth.”

The journey: dynamics, highlights, definitive moments…

Every journey comes with its major moments, spectacular highlights and unforgettable memories. Dr. Bayo’s wasn’t any different. As someone who, at first objected to learning sign language, he is particularly emphatic about the role of sign language and specific individuals (Riskat Robiu,etc) in the process. He shares memories of discrimination, amusement, and the lessons gleaned.

“I couldn’t use sign language when I got to Federal College of Education (Special), Oyo. I was always telling the interpreter to go find something else to do. I started learning sign language in 2000 because I wanted to be of help to Deaf students in the college. I used the book, Joy of Signing and with lots of encouragement from fellow students. However, my first contact with sign language was through Riskat Robiu. She taught me the alphabets when she visited our house in Abeokuta.”

“Ope-Oluwa Sotonwa and Bamiyo Ogunrunde played a big role in my learning sign language and adapting to the Deaf community. The efforts of late Yemi Sokale and Dr Tola Odusanya can never go unappreciated. The enigmatic Dr Odusanya almost detached my shoulders from my body in the forceful bid to make me sign language. Learning to sign took a lot of burden off me academically and socially. I benefited more from lectures and my interaction with others improved significantly. If I had known, I would have learned how to sign earlier!”

“Being able to understand sign language helped me to be of use to others, stand against discrimination, advocate for my right, and broadened my horizon on issues I wouldn’t have understood.”

Meeting Discrimination

“If I had to focus on discrimination, it would have robbed me of the strength I needed to excel. Some people will even be talking against me in my presence. I coped by not focusing on the past, but instead looking at the brightest part awaiting me in the future.” – Dr Bayo

With those lines, this Deaf academic makes clear why he doesn’t dwell too long on discrimination, although he admits facing it. For this series though, he was willing to share an experience he wouldn’t forget in a hurry – a lesson in looking forward with optimism and a caveat to ableist stereotypes.

“I had just got admission at the college of education. After the lecture, course mates approached me for conversations. When they noticed I am deaf, those who could sign tried communicating in sign language. But I couldn’t fit in as I didn’t understand sign language then. One of them fired a mocking shot: ‘what do you come to do here’, he sneered. ‘You can’t hear and you don’t understand sign language’. ‘Do you think English department is for people like you?’ Odd enough, I didn’t get angry. I smiled and told him to wait and see. At graduation, I was the overall best student in English department and others. That same sneering guy came to me and said “Bayo, I never thought you were this dangerous!” I smiled again and shook hand with him. We are still friends today.”

Academic Upshot – When one door closes, another opens

After the FCES experience, the young man continued up the academic ladder with a steady, focused climb – bagging a first degree in 2004 (University of Ilorin), a masters degree in 2010 (University of Ibadan) and in 2024, a doctorate degree (Lead City University). Sharing the motivation and lessons learned from his academic achievements, he said:

“I was able to understand two axioms. First: “when one door closes, another opens” – It has always been my goal to be a medical doctor. But somehow [perhaps owing to earlier disillusionment related to deafness], I didn’t reach that goal. However I went further till I became a doctor – a different kind of doctor. Another door opened to me in the field of special education and I seized the possibilities it offered to become somebody in life.The second axiom: “where there is a will there is hope” taught me that if I had the resolve to succeed by not allowing disability to wreck my ambition, I could still achieve something in life.”

Today, this unassuming Deaf scholar now teaches at the Federal College of Education (Special), Oyo – the very institution he initially kicked against but would eventually become a bedrock in his personal and professional upward swing. With no alibi for deafness, Dr. Bayo easily stands out as one of the best minds in the history of the college – right from his student days.

Paying it forward…

But he is modest in talking about his achievements. I asked him to share the driving philosophy of his life, he says:

“We measure life not by gain, nor by wine drunk, but by wine poured forth. This is a yardstick I always used to gauge my achievements in life. I don’t see my achievements in terms of what I have gained or where I am today. I always think of where it all started, what I have invested, the challenges I passed through and how I scaled them. I love the biblical admonition to sow my seeds. So, I am still pouring forth wines. It is a guiding principle that really defines my way of approaching whatever I set my heart on.”

Deafness helped him develop character

Dr Bayo’s lived experience amplifies the view that disability has a way of bettering character.

In the years before deafness, the young Bayo, a carefree soul, didn’t mind consequences of his words and actions. Disability taught him empathy. An incident from his college days illustrates this:

“I was going to shower when I remembered that I had forgotten my dettol (water disinfectant) so leaving my bucket of water right there, I ran to get the dettol. When I came back, the bucket had been upturned and my water spilled. Enraged, I rained curses. But the older students came up to explain what happened: A blind student had bumped into my water bucket. I got it fast and my anger abated. I even went looking for the blind student and apologized.”

“That incident helped me to learn empathy for all disabilities”, Dr. Bayo concludes.

Finding humor and gains in the storm

While running this series, I have been drawn to sober reflections on the winning attitudes individuals employ to navigate the labyrinths of disability. Morals from these reflections show that having a sense of humor and an ability to appreciate subtle gains in one’s disability make great assets. Dr. Bayo shares a couple insights from experience:

”One day, my colleagues [some of whom could sign] were discussing. I was there, but no one thought to carry me along by signing. After some time I stood up to leave, and, pretending to be angry shout out: “I can tolerate anything from you, but I will never allow you abuse my father in my presence.” The group was shocked, and, switching to signing made desperate attempts to explain what the discussion was about. My emotion was one of celebratory conquest as those colleagues sweated it out to convince me they weren’t abusing me or my father. I broke out laughing, knowing I had played a fast one on them. At that moment, they got the drift and joined in the humor. But from that day they were careful to use sign language whenever I was in the group. I became known as the guy who alleges abuse of his father to protest being left out of group conversations.”

Furthermore:

“As a student, I could read anywhere. I could sleep in the hostel even with all the noise around. This helped to concentrate mainly on my studies, and, compared to my hearing friends, the results I got at the end [of the day] always gave me a measure of satisfaction.”

Advice to younger generations of PWDs

Drawing from his experience, Dr Bayo tells the upcoming gerations to maintain a positive mentality and refuse to be looked down on anyone to look down because of disabilities. “Be assertive, and firm enough to say NO to what you don’t want.” Work hard and beware of shortcut to success. He advices the young to avoid crime and embrace the virtue of patience with the acronym: “

Patient Until Something Happens.”

Addressing a discriminating society

“Disability is not a curse. It is not a disease. It is not something that one should be ashamed of. Much depends on how parents manage the disability of their child/ren from the time they are small. This will determine what they turn out to become in future. Those discriminating against PWDs may be the one who will be discriminated against tomorrow.”

Waxing a bit theological, Dr Bayo admonishes:

“Everyone is equal before God. The Good Book commands ‘not to do or call down evil on the deaf nor put stumbling objects in the way of the blind’. This shows clearly that God does not discriminate against people with disabilities so why should some people be doing that?”

He closes with:

“The world will be a better place when everyone begins to see and accept PWDs as belonging to the main society, and not just a microcosm of it.”

The Disability Champions Series, a collaborative project with Madam Joy Bolarin, Executive Director, Jibore Foundation, is anchored by Ogheneruemu Alexander (Disability issues blogger).

Special acknowledgement to T.O.L.A Foundation for constant back up support.