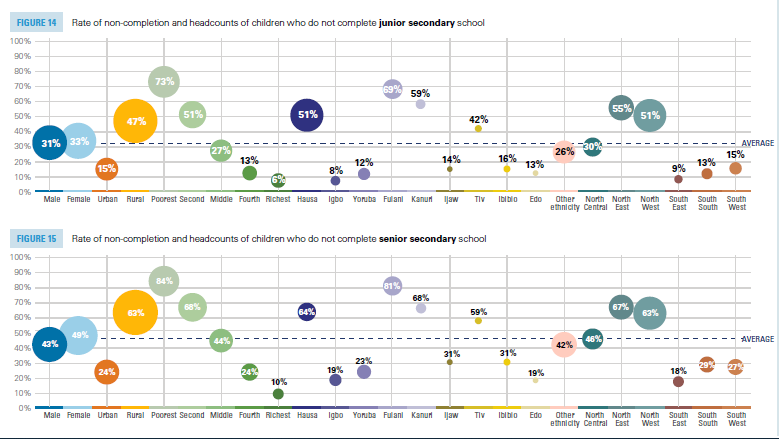

For every classroom of Nigerian girls, nearly half will never sit for their final secondary exams. According to a 2023 Nigeria Education Fact Sheet published by the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) in April 2024, which analysed learning and equity using NBS’s MICS data of 2021, the non-completion rate for girls is 33 per cent at junior secondary level and rises to 49 percent at senior secondary level, compared to 31 per cent and 43 percent for boys. This gap, though seemingly small on paper, translates into millions of girls whose futures are cut short simply because of their gender.

Education is not a privilege but a fundamental human right. Section 18 of the Nigerian Constitution obliges the state to ensure equal and adequate educational opportunities for all. Similarly, CEDAW, under Article 10, commits governments to eliminate discrimination against women in education, while the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights, in Articles 17 and 18(3), reinforces the right to education and the duty to protect women’s rights. Yet the gender gap in school completion shows that these commitments remain far from reality.

Although education is often described as the key to opportunity, for too many Nigerian girls, that door closes far too early, leaving them more vulnerable to child marriage, gender-based violence, and economic dependency. The human cost of these lost opportunities is profound, and the national cost is equally devastating.

The reasons why girls drop out more frequently than boys are numerous and deeply rooted in cultural, social, and economic barriers. Poverty remains a powerful force; when families cannot afford to send all their children to school, sons are often prioritised. Girls disproportionately shoulder household responsibilities, often missing school to care for siblings or assist with domestic chores. Period struggles, made worse by a lack of sanitary pads and inadequate facilities, also force many girls to stay away from classes. Early marriage and pregnancy cut short the education of thousands of girls every year. Digital exclusion makes the gap even worse. With only 6.2 per cent (according to MICS 2021 data) of young women possessing basic ICT skills compared to 9 per cent of young men, Nigerian girls are further locked out of future opportunities in the digital economy.

In regions where abductions and attacks on schools have become a frightening reality, parents are often reluctant to allow their daughters to continue their education for fear of harm.

When girls leave school early, the consequences extend beyond the classroom. They lose access to remote learning, digital entrepreneurship, and tech-enabled careers. Their exclusion from online spaces reduces participation in democracy and silences their voices in public life. The cycle often continues with child marriage, poverty, and limited economic independence. The impact is generational, affecting not only the girls themselves but also their families, communities, and the nation’s development.

Yet, amid these challenges, there are rays of hope. Initiatives such as UNICEF’s Girls’ Education Project and Nigeria’s Safe Schools Initiative are working to keep girls in classrooms. Local organisations and individuals are launching programmes that provide free sanitary pads, mentorship opportunities, and community awareness campaigns aimed at dismantling the stigma around girls’ education. These efforts are critical, but they are not enough on their own.

To truly close the gender gap, Nigeria needs stronger enforcement of child marriage laws, greater investment in safe schools, and policies that reduce the financial burden on families. Community sensitisation campaigns must work with grassroots initiatives to change perceptions and demonstrate that educating girls benefits everyone. Also, menstrual hygiene management programmes must become a standard part of educational policy to ensure girls can attend school without shame or disruption.