When William tells his story of struggle and triumph, he does so with a special bias for the powers of the “delphic” and “a resolute will”.

There are people you come across – whose life story and adventures simply transcend the bounds of time and space. These people aren’t necessarily super-humans possessing some extraordinary abilities. Yet certain events and circumstances of their lives leave eerie traces of silent mysteriousness – an uncanny quirk for surviving situations that will snuff the life off the typical mortal.

These Delphic souls, they are like the proverbial cat with nine lives. They land on their feet after falling from dangerous altitudes. They survive a fire. And when you think they are lost, they show up. Okay, they have just one life, literally, but figuratively, they live nine lives. They dine with the gods.

William Olugbemi Olubodun, our feature hero in this 13th of the Disability Champion Series fit well into this category of indecipherable personalities.

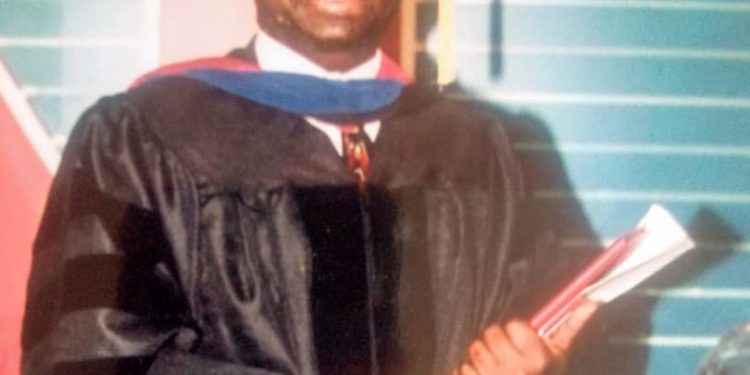

I had the opportunity of a private interview with William at his Odeda, Abeokuta home town. During the interview, we explored select highlights of the journey through daunting odds to reach the enviable heights he accomplished. William, now retired after years of sojourn and service in far away United States of America, proudly holds a bachelor’s, two master’s and a PhD degree.

No mean feat for an erstwhile deaf farm boy who had but a “snowball’s chance in hell” under the circumstances and environment he grew up in.

It was an emotional time listening to the soft-spoken, suave sextagenarian share the intriguing story of his charmed life – a testament to the classic delphi’s trait of mysteriousness (in the context of African traditional beliefs) and a resolute determination to survive against all obstacles – overriding themes in this story of a scarred veteran of the disability struggle.

“In the family compound he grew up in, William remembers being flanked as if in war formation (with himself as the star studded general confidently advancing to war) by “orisas” – Obatala (Yoruba god of creation) to the left, Ogun (god of war) to the right and Araigbo (forest deity) at the rear.

Such was his attachment to these deities. And this made enduring impressions on William’s world view on the influence of a Supreme Deity and lesser ones in his odyssey.

The phenomenal childhood years

William holds sweet memories of his early childhood years – especially as a hearing kid. Although these memories would turn bitter when deafness struck – either way, an outstanding hallmark of those years remains how deeply steeped in the tapestry of a typical traditional African communal setting they were.

“I was born in Mogan village in Odeda Local Government Area of Ogun State. My childhood years were unbelievably beautiful. Growing up in Mogan village was like living in a protected haven – a joyful, carefree world where we roamed about nonchalantly and oblivious of dangers”.

With those words, William recalls the close-knit, communal setting that shaped his early years. The young boy was a favourite among the rural dwellers – especially the elders by virtue of the extraordinary circumstances of his birth (he had survived infant mortality) and certain precocious traits that stood him out. Right from a very tender age, he showed an unusual interest in schooling and was one of the star pupils in the village primary school. He had a special rapport with the “Baale” village chief and “Iyanla” big mother (one of the oldest women in the village). Among these elderly folks, young William attracted a kind of regard not accorded to the other children. He would be nicknamed Salako “special creature of Obatala” and believed to be a reincarnation of his grandfather the immediate past “Baale” of the village. But the fire accident that left him deaf – with a horrifyingly scarred face would abruptly turn the tide against him.

Turning point

“My work cloths were drenched in gasoline…without warning a spark ignited and I was engulfed in flames. I was taken to the Lagos University Teaching Hospital and left for dead”.

It was Monday, January 19, 1970 and will forever remain etched in William’s memory. That day, while working as a motor mechanic apprentice aged 13 or thereabouts, a fatal fire accident occurred that would mark a turning point.

Fatal… The enormity of that accident would have snuffed life off a less charmed mortal but not this delphic conqueror’s. William survived the death scare. After nine eventful months (including an out of the body experience) in a hospital ward, he came out permanently scarred and deaf (the result of prolonged administering of various injections and antibiotics).

Disability, discrimination, superstition

Back in the village after discharge, William’s previous privileged standing met a rude twist. Suddenly, Mogan’s child prodigy became an “oloriburuku” (person with a bad karma whose life was meaningless), and was called an “unfortunate”, amongst other derogatory terms. It didn’t take long for the teenage boy to realize that an uphill road lay ahead. A few years earlier he had finished primary school but couldn’t proceed to secondary because his father was reluctant to send him – citing financial constraints. Now he was deaf, there was an added alibi why the young boy should forget about schooling.

“Anyone who could not hear, his life was over”. That was the consensus among these rural folks in those days…

Curious, I asked how he managed this contrast of circumstances.

William’s response resonates the potency of “resolute determination” and the “interventions of Providence”. But first, he eulogizes the influence of a loving mother:

Mother was a backbone

“This is your true son…he became deaf. Everyone of you thought his life was over but now he found himself again. I do not know that “aditi” can go to school. He is your son!”

With those words, William’s mother reprimanded a gathering of villagers skeptic of his son’s chances of returning to school to pursue a threatened academic ambition. It was the love and constant prodding of this uneducated mother that helped lay the first foundations of his academic achievements. And when the young boy became deaf and almost everyone in the village thought his life was over, it was this same unflinching support of a mother that would see him again find himself.

“How could I not cherish such a mother”, says William.

It must be re-emphasized at this point the role of amazing Providential interventions in this champion’s odyssey. Notable among these was the miraculous provision of funds and favors in most unexpected ways for his academic upswing – from secondary through tertiary years. William acknowledges the influence of guardians and supernatural forces being actively at play in his life story – veiled references to the Delphic.

Still, to his credit William evidenced a resolute determination very early in life – a strong factor in meeting the challenges that came with deafness. Referring to this, an elder rightly observed: “You cannot tame a tiger or warthog”. William would go on to prove that statement true.

Leveraging disability to build character

Don’t say you are having a bad day, say you are having a character building day!

One of the finer traits of champions is their knack for finding some good in apparently bad situations. William has this in abundance. He recollects that even as a child he never accepts a situation was bad but finds something useful from it – little wonder then the lyrics to one of his favorite hymns perfectly aligns:

”Since all that I meet, shall work for my good. The bitter is sweet, the medicine, food…”

William ardently believes in the saying: “every bad situation is an opportunity to get stronger, better, and build yourself up”.

He recalls those sad days in the village after deafness literally consigned him to the drudgery of farm work and bricklaying: “in my frustration and loneliness, I began to immerse myself in extra activities, at least to keep my mind off the seemingly insurmountable odds around me. I wove baskets and soon my baskets became so popular in demand. I learnt hunting for venison”.

These activities not only built my character, they helped reduce suicidal thoughts.

“Deafness taught me patience and tolerance”.

Though I was deeply hurt by the discrimination and intolerance, I learned to endure and roll with the punch. In the quietness of deafness I developed focus, I felt God used that eerie silence to make His presence real in my life – indeed much of the fanciful dreams and day-dreamings had in the quiet of deafness would become future realities.

Is Disability a bad thing?

At this point, I asked the elderly gentleman an unusual question: So, is disability a bad thing?

William answers, speaking for himself. “I wouldn’t say disability is a bad thing. In my case, I was quick to accept my deafness and that expedited my progress”.

Then he goes philosophical: “Providence used my disability to grant me the success I achieved”.

He concludes with the advice: “If you ever wake up one day and find yourself with a disability, get down on knees and thank God”.

Coping with Discrimination

If anyone has experienced disability based discrimination, William has. He recounts a number of hurting, humiliating incidences that pictures the struggles of being deaf in a hearing society. How does he cope with these? His response is amazingly generous, devoid of bitterness – throwing a subtle challenge to persons with disabilities themselves: “These (hurtful experiences) are tolerable, because if they (a discriminating society) knew better, I would never have been treated anywhere close to that”.

Advice to younger generation of PWDs

Drawing from his rich lived experience with disability, William shares general lessons learnt on the way up. He places premium on punctuality, patience and a readiness to take on any honest job – however lowly. “Patience is a virtue”, he reiterates. A man without patience is as a lamp without light.

But don’t be afraid to start small, persevere through the pain and peril as work your way up. Do not feel above any honest labor. And reminds that these principles will work irrespective of disability.

I drew the interview to an end by asking William’s perspectives on society’s obviously exaggerated responses of “being inspired” by people with disabilities who achieve in life (termed “inspirational porn within the disability movement).

William does not feel offended by that. “That’s okay”, he says, “it’s all part of how Infinite Intelligence works. People are bound to be surprised on witnessing what exceeds their expectations”. He strengthens this view using the instance of the fire accident at the mechanic workshop when he taken to the hospital and left for dead. Placing this against the backdrop of his extraordinary comeback, he captures the reactions of the people around in an interesting way: “They don’t know what to do with me again “.

The Disability Champions Series, an initiative of Jibore Foundation, is anchored by Alexander Ogheneruemu, a Deaf writer. Special acknowledgement to T.O.L.A Foundation for constant backup support.