This is the second part of this report. You can read the first part here.

Kingswill: Operations in Secrecy

James, George, and Obi have common tales of urban poverty. Aware of the near impossibility for many young Nigerians to earn a decent wage and the pressure to keep up with global consumerism, operators of surrogacy in Nigeria go for the jugular of vulnerable women, like the ones seated clutching their appointment cards like regular visitors to a hospital.

However, I observed that all of them were hiding their cards, especially to conceal the front part. I wondered why since they were inside the clinic and everyone was there for the same purpose.

“We have been told not to expose the name of the clinic because it is on the card. Even when we are here or outside, we are used to hiding it,” James explained.

“You also know that it is not appropriate for people to see our cards so they won’t start asking questions about why we’re visiting a hospital or thereabouts.”

Obi corroborated the explanation. She said she usually took permission from work whenever she needed to visit the clinic, not wanting anyone to know what she was doing and exposing the appointment card might jeopardise her chances.

Asked how she would cope with work when she needs to stay in the hospital for multiple days at the point of the egg retrieval, Obi said “I will take a sick leave and take a picture of myself on the hospital bed. I am sure my boss will even give me money to pay my hospital bills.”

Her statement made me wonder if truly her salary was not sufficient for her, or if she was just interested in doing what others were doing.

The appointment cards were also used as wallets to pay the donors. The nurses would enter the small room, collect cards from people depending on their appointment stage, and return the cards with money.

After opening the cards, the women were usually seen calculating how much they had collected so far as transportation costs and how much more to expect.

After a lot of zooming in and out on the appointment cards, my spy camera revealed the name of the clinic as Kingswill.

Spotlighting Kingswill Clinic

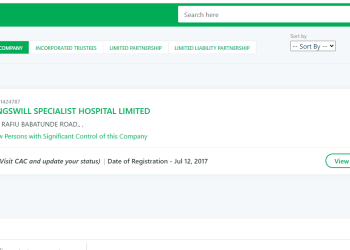

A public search on the Corporate Affairs Commission’s website revealed that Kingswill Specialist Hospital Limited was registered in July 2017 as a Private Company Limited by Shares with registration number 1424787. However, the status is inactive and the purpose of operation is NIL.

I checked through the organisation’s website on 20 May and it indicated that they offer IVF as a service. When I checked the website again on 7 July to extract more details, the website had been suspended by its hosting platform due to non-renewal.

On the other hand, the hospital does not have the logo of the Health Facilities Monitoring and Accreditation Agency (HEFAMAA), the agency saddled with the responsibility of monitoring both private and public health facilities to ensure registration and accreditation of all health facilities in Lagos State, and to ensure their operations are in line with ethical standards.

Speaking with Yemisi ‘Koya, the chairperson of HEFAMAA, during a stakeholders’ engagement workshop organized by HEFAMAA, she explained that “whichever hospital where you do not see a logo of HEFAMAA, that means that facility is not registered by HEFAMAA, please do not go there.”

“If there is anyone that has HEFAMAA’s logo but is involved in illegitimacy, please report to HEFAMAA,” she added.

Speaking about malpractices in facilities registered under HEFAMAA, Mrs ‘Koya said: “The law empowers HEFAMAA to conduct at least two facility visits per year, and we did engage the collaboration of stakeholders; franchise organisations to expand our reach to meet the mandate of the regulation.”

Through this regular check by HEFAMAA and the franchise organisations, the agency is able to beam its search light on illegal health facilities and stop its operations.

In the same vein, Abiola Idowu, the Executive Secretary of HEFAMAA, said the agency was also counting on intelligence sharing from members of the public who might be aware of baby factories in the name of fertility clinics or fertility clinics operating illegally.

“We regulate fertility clinics, they fall under the Artificial Reproductory Therapy (ART) facilities and it is part of HEFAMAA’S regulatory oversight, so we set out standards for them. If we find any facility that is not operating according to the guidelines or is not registered, we will sanction them.

“I will enjoin the public if they see any facility that is running as a baby factory, they should let us know. If they see any facility without our logo or without our certificate pasted at their entrance, they should report to HEFAMAA,” she added.

However, when I presented my findings and the name and address of Kingswill Specialist Hospital to HEFAMAA, the monitoring unit of the agency confirmed that the facility is registered with HEFAMAA and is up to date with its annual renewal payment as of last year.

Mrs Idowu, however, noted that my findings would be passed to the ART Committee, which is under the board of HEFAMAA, to conduct necessary investigations.

“Immediately we got your message, we are checking their registration for this year, and if there is any deficit. We have also kicked off our investigation, whatever the outcome is, we will let you know,” she said.

While Kingswill Hospital might be run by professionals and accredited by HEFAMAA, its mode of engagement with innocent young women as oocyte donors and surrogates, and without proper enlightenment, is unethical.

When I contacted the hospital, officially, for comments about the unethical practices and lack of informed consent for donors, the receiver who sounded unsettled after I explained the purpose of the call asked me to call back in five minutes. When I did, the line became unreachable. I sent a text message and received feedback the next day, from a different number, but with the hospital’s signature.

I was assured that an appointment would be scheduled and I could speak with the hospital management. But I did not get any feedback after many follow-up texts and calls. On the third day when I reached out, another woman picked up the call (on the new number) and said I would be contacted. However, I have not received any feedback as of the time of this report.

My turn: No enlightenment for donors, poor attitudes of medical personnel

It was already past 3 p.m. and there were just six of us in the room, including my friends and Obi. The nurse who had been hostile and shouting at every provocation became calm and told me she was assisting me because they don’t take new intakes on Saturdays. She asked me to use the bathroom after which I would see the doctor.

She asked if my friends were egg donors, but I said no, that one of them was pregnant and she wanted to ‘give it out’. She corroborated what the agent told me via chat some minutes earlier, as the agent had offered to link my friend up with someone else in Anambra who would adopt the foetus.

After our conversation, the nurse hurriedly directed me into a room to meet the doctor and told me to beg the doctor to attend to me, because the doctor was not obliged to attend to first-timers on a Saturday.

I wasn’t sure of what to say or ask at that point so I remarked that ‘I am on my period’. She said that was okay and that I should proceed to meet the doctor.

I entered the small testing room where I was supposed to meet the doctor, but I didn’t see anyone and I thought I had missed my way. I stepped out of the room, opening another exit door that linked to the hospital’s lobby. I saw a couple entering through the main door, it was obvious they were seeking one of the services of the fertility clinic.

While wandering and trying to identify the doctor’s office, I was hushed and directed by the other nurses and asked to go back to the testing room I came from. I went back into the room which had a small bed, a trans-vaginal ultrasound scanner, a table and a few items placed in the wardrobe section.

After waiting for about 10 minutes, a female doctor, beautiful, fair and petite came in. She did not ask too many questions, but also verified if I was menstruating and if I had given birth before, both to which I said ‘Yes’.

She placed a mackintosh on the bed and asked me to lie down for a test and to remove my underwear. I reminded her that I was on my period and asked about what she wanted to do. She told me she wanted to test me. I asked a lot of questions, but she was not interested. All she wanted to do was to conduct the vaginal scan to ascertain if I was ‘okay’, could proceed with other blood tests and begin treatment.

To do the vagina scan, she would insert the ultrasound probe (transducer), covered with a condom, into my vagina. I genuinely tried to do the vaginal scan, but I couldn’t imagine the procedure. On the other hand, the doctor was not sure why a lady who had supposedly given birth before would be cringing all because of a vagina scan. I gave her the excuse that I was menstruating and I found it irritating that she wants to do the scan.

Obviously displeased, she shouted at me, saying “I should be the one to complain that you’re on your period. If you’re not ready, I will walk you out and never come back here.”

She told me if I ever came back, she would be the one to attend to me, and she would need to conduct a vagina scan on me during my menstruation. She thought I was one of the desperate women who dared not complain whenever nurses or doctors treated them badly. I wondered why the doctors or the nurses wouldn’t take the time to enlighten a surrogate or donor about the steps they were taking. I believe they were only interested in making money and not in the welfare of innocent young women.

I left the room. Of course, I was not interested in going back to the hospital. As I got back into the room where the women were, the doctor came in to complain to the others and the nurses about my bad attitude and how I was not ready. The people in the room could not fathom why I declined. I also do not know why, but I guess I was not mentally prepared for it. I was not ready to go through any form of psychological trauma after the vagina scan.

My experience in the room confirmed that surrogates or egg donors were not informed about the life-altering decisions they were taking and they were definitely ignorant about the long-term consequences and health risks involved.

Simbiat Bakare, a sexual and reproductive health rights advocate, decried Kingswill Hospital’s approach and that of any other fertility clinics that do such.

Ms Bakare described surrogacy as “another form of organ trafficking and modern-day slavery. It is harvesting (poor and young) women’s eggs and wombs. In some instances, it is the usage of both of a woman and, in other instances, it is getting the eggs and renting the womb from multiple sources.

“It is deeply disturbing to think that sometimes multiple strange women’s bodies are used to produce babies for wealthy couples or all the reproductive facilities of one woman are used to give a child to a richer person. Because for a fact, we know most of the women used as surrogacy mothers and egg donors are young women in need of financial assistance.”

The SRH advocate added that “like prostitution, it’s an institution taking advantage of the most vulnerable set of women in society either due to their lack of access to credible information, money, naivety, or a combination of all.

“Although some may argue that surrogacy can be altruistic, it doesn’t change the fact that it’s deeply unethical and like all forms of organ trafficking, it must be stopped. Having a baby is not a human right. It might be a desire or a want, but it’s not a right.”

Human Cost: Health and Emotional Consequences

There are short and long terms physical risks and complications faced by surrogates and donors. These include psychological and emotional toll on participants in surrogacy arrangements as well as lack of post-surrogacy care and support for the women involved.

According to Public Health Post, “Egg donors have reported long-term effects including aggressive breast cancer, loss of fertility, and fatal colon cancer, sometimes occurring just a few years after donation. Without any family history of these illnesses, they suspect their egg donation as the cause. However, without scientific research, no one can confirm or deny a causal association between the medical procedure of egg donation and any reported long-term effect.”

Regarding the emotional consequences, Dayo Odukoya, the founder of Parah Family Foundation, an NGO that creates awareness among couples going through infertility challenges, said some of the measures that fertility clinics and surrogate agencies take to cut off ties between the surrogate mothers and babies, include delivery through Caesarean section.

“They don’t allow the surrogate mothers to see the baby after being taken out through Caesarean section. They don’t want the woman to hear the first cry of that baby or breastfeed the baby at all. This is to avoid any form of bond between mother and child.”

Mrs Odukoya thereafter noted that these terms are usually known by both parties and should prepare the donors before getting started.

However, James didn’t have all the information to help her make an informed decision prior to her first surrogacy contract, although she didn’t seem keen on knowing too much as she was in it all for the money.

According to her, experience is the best teacher. She believed she was better prepared for her second surrogacy contract, which might possibly be her last, but also she was unsure.

“I have a child before which I delivered through natural birth. This is my second surrogate process and if I deliver through CS, I might not be able to do another one. I also want to give birth later in the future and I don’t want to ruin my chances,” James added with so much uncertainty.

George wasn’t worried about any health complications. According to her, “You have to take a break for about two or three months before another egg donation so that the eggs can be many before the donation.”

This is the second part of this report. You can read the first part here. The concluding part will focus on ambiguous laws and illegitimate practices leading to health risks and emotional trauma for surrogates and donors.

Editor’s Note: All the names of the donors in this story are not real names, to protect the identity of the ladies.

This report was supported by the Wole Soyinka Center for Investigative Journalism (WSCIJ) under its Report Women! Female Reporters Leadership Programme (FRLP), champion building edition.